“The overrepresentation of young Aboriginal people in residential care and limited access to appropriate services are pressing issues. While Aboriginal organizations, service providers and the Ministry are involved in a number of initiatives to address these issues, we were very concerned by the persistence of the issues that were raised about the experiences of young Aboriginal people placed far from home, community and culture.” – Because Young People Matter, February 2016, p. 74

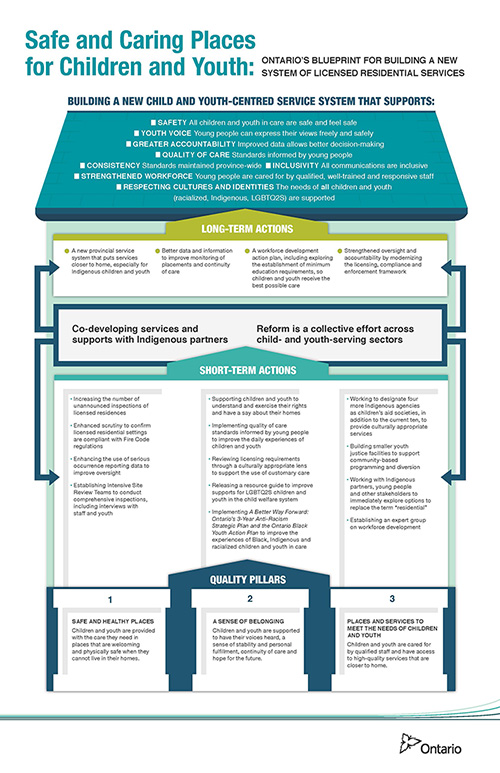

On July 19, 2017, Ontario released their multi-year plan to

strengthen and reform licensed residential services by seeking to improve the

quality of care, enhance the oversight of services and ensure that children and

youth have a voice in helping plan their care (by 2025). All of the reform

activities outlined in this Blueprint (a three-pillar strategy) will impact

First Nations, Métis and Inuit children and youth that are in care of a

provincially licensed residential facility.

The impact that this blueprint will have on Indigenous communities

was central to the strategy itself – which is why the Ontario Indigenous Child

and Youth Strategy (OICYS) served as the foundation for co-developing services

and supports. The OICYS is a short vision document, and this blueprint

represents an exercise of the principles contained within it. The document

asserts that this will allow for First Nations to co-develop

Indigenous-specific and culturally appropriate strategies and approaches to

better serve our children and youth. Furthermore, one of the guiding principles

for reform is “Respect for the knowledge, customs and rights of First Nations,

Métis, Inuit and urban Indigenous communities”

This process that led to

this report’s release began with the May 2016 Residential Services Review

Panel’s Report, “Because Young People Matter.” That mandate was to continue

work that would provide advice on improvements to residential services for

children and youth. It made recommendations in ten key areas, including First

Nations, Metis, and Inuit young people in residential care. This report specifically

pointed to key issues in 1) overrepresentation of Indigenous people in

residential care and 2) lack of access to appropriate services.

Many youth in provincially

licensed residential settings in Ontario have experienced chronic stress,

cognitive, physical and mental challenges, abuse, and other trauma. Alongside Ontario's

three-year Anti-Racism Strategic Plan, the overarching goal of this blueprint is

to reduce the overrepresentation of Indigenous and racialized youth in the

child welfare system.

The Residential Services Panel (made up of 12 youths aged between 18-25 from across Ontario with experience in residential care system) was brought together by the Ministry of Children and Youth Services in July 2015 to conduct a system-wide review of the Province’s child and youth residential services system, including foster and group care, children and youth mental health residential treatment, and youth justice facilities. The Panel reviewed foundational materials supplied by the Ministry, including previous reviews and background briefing documents. Consultations were also held with stakeholders and partners across the province representing young people, families, caregivers, front line and agency management staff, professional associations and government staff. A total of 865 people participated in the consultations, including 264 young people.

Three Quality Pillars for

Reform:

The strategy is built

around three pillars that, if upheld, would allow “the fulfilment of their

(young people’s) individual and unique potential.” They are:

- Safe and Healthy Places - this refers to physical safe space

- A Sense of Belonging - this refers to the available culturally appropriate support

- Places and Services to Meet the Needs of Children and Youth - this refers to the right to have access to services appropriately

Short and Long-Term Goals

The Blueprint identifies

short and long term goals which will guide revisions of Residential Care. While

the short term goals are tied to the three Quality Pillars for reform, the long

term goals are higher level.

The short term action items include:

- Safe and Healthy Places

- Building Oversight: The province will undertake a number of initiatives to identify areas of risk, and to ensure that all residential services are compliant with safety regulations. This includes increasing the number of unannounced inspections of licensed residences, establishing intensive site review teams, increasing scrutiny on fire code regulations, and implementing new authority for the Minister to inspectors.

- Information Management: The ministry is developing approaches to track and monitor the movement of children and youth, automating the Youth Justice Services experience survey, and develop a “risk-based licensing framework.”

- A Sense of Belonging

- Developing Resources for Children and Youth: The ministry will make the Blueprint available as a "child- and youth-friendly resource" in accessible language (Oji-Cree, Ojibway and Inuktitut), develop a “rights resource” so children understand their rights,

- Developing Mechanisms for Input into the System: Mechanisms will allow for youth currently in the system to provide feedback (such as Youth councils), and for those who used to live in the system to provide perspective on the system.

- Indigenous Programming: Licensing will be reviewed “through a culturally appropriate lens”, and the Ministry will explore “how to better support Indigenous service providers,” especially in Northern Ontario and the Ottawa area.

- Places and Services to Meet the Needs of Children and Youth

- Immediate action is being taken within the current legislative framework (The Child & Family Services Act) to collect better data, establish four more Indigenous agencies as children's aid societies, build smaller youth justice facilities, and map existing residential services.

- Replace the term “residential.”

- Establish an expert group on workforce development to improve the quality of staffing

- Minimize the use of physical restraint

- Implement new information sharing provisions within the Child, Youth, and Family Services Act

- Co-develop strategies and approaches with Indigenous partners, under the OICYS.

Longer term goals are subdivided into three categories:

- Effective Service System Planning and Management

- Accountability and Oversight

- Workforce Development

Highlights concerning First Nation residential services (as guided

by the OICYS) include:

Developing

specific approaches focused on residential services that will empower

communities to make decisions regarding, and care for, Indigenous children and

youth,

Enabling

First Nation children and youth to remain in their home communities,

Impact on First Nation

Communities

This Blueprint is difficult

to assess as it relates to First Nation children and youth because it is in

many ways an aspirational document. The position of First Nation children and

youth in the system is front and center in the Blueprint, but it lacks concrete

actionable items to assess. This Blueprint should, then, be viewed as a tool

which First Nation leadership can use to achieve key goals concerning child

welfare.

Jurisdiction: This

Blueprint is informed by the OICYS, which contains as a key pillar “First

Nations Jurisdiction and Control.” Chiefs in Assembly Resolution 11/32

establishes principles regarding child welfare, namely that “First Nations have

never relinquished jurisdiction over Child Welfare.” Still, section 88 of the Indian

Act provides for application of some provincial laws on reserves – an amendment

passed in 1951 without consulting First Nations. Resolution 13/27 (“First

Nations Jurisdiction on Child and Youth Services”) further instructed the

Chiefs of Ontario to work to implement the “Children First” report

recommendations – part of the Aboriginal Child and Youth Strategy in Ontario.

At the meetings described in the resolution, representation from the PTOs,

IFNs, Six Nations of the Grand River Territory and Mohawk Council of Akwasasne

all indicated that they hold jurisdiction over all matters concerning their

children.

The recommendations within the Blueprint leave a window to

meaningfully exercise the existing First Nation jurisdiction over child

welfare, which can serve as an avenue for self-governance. If the commitment to

develop indigenous approaches that would empower communities to make decisions

regarding children and youth in care is made in good faith, the clearest path

to achieving that goal is to recognize that this is an avenue for the tangible

exercise of self-governance by First Nations. Currently First Nation agencies

operate within the confines of the Child, Family, and Youth Services

Act (2017) with an authority akin to Children’s Aid Societies. There

may be potential to develop Indigenous legal frameworks within which child and

youth services could operate.

Funding: Immediate

and long term commitments within the Blueprint repeatedly indicate the

intention to work with Indigenous partners in co-developing programs and

strategies to more effectively address First Nation children and youth’s needs.

This Blueprint would also be an avenue through which funding committed in The

Journey Together will be allocated. Specific funding levels are not

identified in this Blueprint.

Oversight: The Blueprint provides for First Nation oversight of agencies that

work with First Nation children and youth. The details of this oversight are

not identified, as they need to be developed with Indigenous partners.

Access to Resources: Youth should have ease of access to resources, services, and

opportunities to help shape a more cohesive child welfare system. A gap in the

current system fails to better coordinate the support and services provided by

various care-givers to one youth - e.g. the tutor and mental health worker

should come together to create a coordinated plan rather than working as

individual entities.

Staffing of Child Welfare Agencies: To help build capacity in remote and rural areas

and in northern Ontario, the province says they will undergo recruiting and

retaining of "qualified and diverse employees". However, this is not

specific enough. Indigenous communities need to know whether Ontario is

committed to recruiting qualified and diverse employees that are knowledgeable

and sensible (i.e. sensitivity training) enough to work with the Indigenous

peoples. In other words, the best way to resolve this issue may simply be to

find and retain qualified indigenous employees.

Next Steps

The Blueprint outlines a number

of short and long term benchmarks. It indicates that the Ministry has already

modernized the legislation that governs licensed residential care (the

Children, Youth, and Family Services Act, 2017) and has begun working with

Indigenous partners to improve and modernize residential services. Chiefs of

Ontario has the existing resolutions that would support working towards

improving residential services, asserting jurisdiction on reserve and providing

culturally appropriate services off reserve, and securing funding for First

Nation children and youth.

Resources

No comments:

Post a Comment